Assorted Notes from CECS1031

Preface

Dear students and readers,

I had an awesome Fall 2025 semester working as Teaching Assistant for the course CECS1031 Computational Thinking at VinUni. During this period, I spent an meaningful amount of time writing guides and revision materials for the students in that course. I bundled all of them together in this megathread.

Some important notes:

- This isn’t the official lecture notes. The only official materials are the content that Prof. Cha gives. This means that some of the content may be added or removed compared to what I wrote here. I have re-iterated several times throughout that this alone might not be sufficient to get full marks in the exams.

- This isn’t a complete coverage of the course. While I managed to cover a large proportion, it’s inevitable that I have left out some materials. Again, please check Prof. Cha’s slides for the most complete picture.

- This isn’t flawless. I might have made a few mistakes in the original posts (and some sharp-eyed students have pointed out to me). If you can spot any error, feel free to reach out and I will correct it.

These materials are supposed to sit between and complement the official lectures and slides (I thought if the students at Stanford and MIT have nicely organized lecture notes, the students at VinUni should too). My original intent was to help students have a good grasp of the most challenging aspects of the course (modules 3 through 7 for the exams, and project #2 and #3) by providing them with beginner-friendly tutorials. I think I have somewhat succeeded in that regard. My hope is for this to be helpful towards future students as well.

That’s all. Good luck and have fun learning.

Son.

Why Computational Thinking? (Module 1)

We hope you’ve got a positive impression from this course. We know some of you are thinking whether you should take this. I can’t give yes/no advice, but I can tell you a bit about why this course might be worth taking.

“Computational thinking” might seem like a strange concept, known only to coders. Java coding probably scares you. But here’s the thing: We don’t expect you to become a programmer. What we hope to teach you is the “thinking” part.

Let’s take an example. When I was eight, my mother requested me to “wash the dishes”.

I used to joke about the literal meaning of that phrase: “I’ll only wash the dishes, and not the bowls, the chopsticks, the pans, etc.” Of course my mom didn’t mean literally “just the dishes”. She is using the phrase “washing the dishes” to refer to the entire process of putting all the equipment we used for cooking and eating into the sink, clean them, then leave them to dry. But it would be a mouthful to say “Son, wash the pans and the pot and the dishes and the bowls…” every meal. Instead, my mother taught me what “wash the dishes” meant, and just used only that phrase afterwards.

This is an example of abstraction: focusing on the most relevant information while leaving out unnecessary detail.

I can extend this abstraction kind of thinking to other examples: When you text your boss, you’ll only say “I’ll send you the report next Monday”. “Sending the report” is an abstraction – how you make the report and when you send it is up to you. It would be burdensome to include all those details into the text message; besides, your boss probably only needs the report, not the knowledge of how you make it. Perhaps you already know this, then you are already using abstraction – now you know it has a name.

But, this knowledge might be useful to your teammate, so maybe you need to tell them what to do step-by-step in great details.

- Collect and analyze the data.

- Create charts to visualize key findings.

- Write a short summary of your analysis.

- Put everything together in a PowerPoint or document.

- Save the file.

- Email it to your boss (and copy other relevant people).

This is what we mean by decomposition: breaking down a problem into atomic, actionable steps. Of course, this is a simplified example, so the decomposition is not perfect. You could, for example, further decompose “Write a short summary” step into small sub-steps like ‘determine key takeaways’ and ‘draft executive summary’.

If you are a seasoned analyst, you know exactly “sending the report” entails. Yet, to young, inexperienced staff, they might need very detailed, broken-down style, step-by-step guidance – otherwise they might miss some steps in a complex process (it happens more than you think).

I hope these short examples are enough to convince you that computational thinking is at least worth a try to learn - because it is not a strange concept, it is already a part of our life. I can give further examples as well, but maybe another time.

Understanding how computational thinking may be useful in real-life scenarios is one of our objectives in this course. Throughout the course materials, we will give you the tools by which you can analyze a situation and come up with “computational” solutions (via explaining concepts like abstraction, decomposition, algorithm, pattern recognition, complexity, and many more). Again, I must emphasize, “computational” doesn’t mean coding – we don’t expect you to code. It’s more or less a structured, logical way of thinking about real world events.

Another thing we hope you learn is the power and limitation of software. Some software (say, AI tools like ChatGPT) are very powerful, but as casual users, we may not fully understand what they can and cannot do (you will be surprised by how bad they are at certain tasks, or how they can be used in harmful way), when to use or not use them. That’s why we have the presentation. We merely ask you to take a look at existing software, try to use them for yourselves, and see what they are like, perhaps do a case study or analyze the impact of those software.

Key concepts from Modules 1-4

To help you review for the midterm, I’ve put together a short recap of key concepts from the lectures. Please don’t rely on this recap alone to pass the test because it can’t cover every little detail, but it’s meant to help you see the big picture of what we’ve learnt. In fact, I have temporarily left out OOP (Object oriented programming) due to time shortage.

Here’s my advice as your TA: at the very least, make sure you understand every item in this list. Search for each item (say, Abstraction, or Loops) in the slides, and consult your favorite AI tool, or message the **teaching team until you have a good grasp of the concepts.

Lecture 1: Introduction to Computational Thinking Concept

- Computational Thinking (CT) is Problem Solving in Software: It’s about figuring out how to design solutions that work well. For example, solutions that are fast, efficient, or easy to scale up. It also means thinking carefully about trade-offs (like balancing speed, cost, or simplicity).

- 4 Components of Computational Thinking

- Decomposition Breaking a complex problem into smaller, more manageable parts. Example: You’re planning a party. Instead of stressing about it all at once, you divide the tasks into:

- choosing a date and location,

- sending invitations,

- buying food and drinks,

- setting up decorations.

Each smaller task is easier to handle, just like breaking a large program into functions.

- Pattern Recognition: Looking for similarities or trends that can help you solve new problems faster. Example: Recognizing that sorting algorithms (like bubble sort and selection sort) both involve comparing and swapping elements.

-

Abstraction: Ignoring unnecessary details so you can focus on the key idea. Example: When giving directions to a friend, you don’t describe every streetlight — you just say “Turn right at the gas station, then left at the school.”

In coding, abstraction helps us simplify complex systems; like using a “System.out.println()” function without worrying how it works inside.

- Algorithmic Design: Developing a clear, logical, and efficient set of steps to reach a goal, while considering trade-offs like time, effort, or resources. Example: You need to get to campus. You have options:

- 🚌 Take the bus (cheap but slower)

- 🚗 Drive (faster but costs more)

- 🚲 Bike (healthy but depends on weather)

Designing your algorithm means deciding which route and method gets you there most efficiently for your priorities. (in my situation, I always take the bus – you might choose different). In computing, algorithm design is the same: choosing between different approaches (e.g., bubble sort vs. merge sort) depending on trade-offs in speed, memory, or simplicity.

- Decomposition Breaking a complex problem into smaller, more manageable parts. Example: You’re planning a party. Instead of stressing about it all at once, you divide the tasks into:

Lecture 2: CT, Generative AI, Security Threats, and Protective Measures

- Understanding Modern Threats: The goal is to understand the main social, ethical, security, and privacy threats in modern computer systems, including False Information, DeepFake, and Voice Cloning.

- Software Vulnerabilities are Widespread: Even software from major companies (e.g., Microsoft, Google, Samsung) has previously undetected bugs and vulnerabilities, necessitating practices like bug bounty programs.

- Generative AI Magnifies Risk: Generative AI technology makes it easier to launch attacks, and Deep Fake technology is becoming more deceptive, leading to a situation where we may “NEVER know for sure what to trust”.

- Serious Intent Behind Attacks: Deepfake technology is often deployed with serious intentions for political, financial, or criminal purposes.

- Asymmetrical Warfare: The reality is that criminals are generally well-equipped, determined, and assisted by powerful technology, often targeting victims carefully with personalized attacks.

- Defense is Crucial: Good understanding of the threat is the first step toward developing effective defense mechanisms, which do not necessarily have to be technical solutions. Detection of fakes is an active, but likely never-ending, research race.

Lecture 3: Basic Programming Concepts with Java

-

Focus on Concepts over Fluency: The primary learning goal is to gain a fundamental understanding of programming concepts and become familiar with Java (e.g., understanding programs). We don’t expect you to code, but we expect you to look at a short program (say, 10-20 lines of code) and understand what it’s trying to do and what it will output; and more importantly, how the output will be different if we change some parts of the code. See the sample questions to get an understanding of our minimum expectations.

For example, if you see this, you should recognize its purpose is to print the message “Hello, world!” on the screen.

System.out.println("Hello, world!"); - Basic Programming Concepts: We’ve covered the building blocks that all programs use. Make sure you understand these programming concepts. If you look at the sample questions, you at least need to understand how variables, loops and conditionals work to trace the program and its output.

-

Variables: Variables store data, like boxes with labels on them. For example:

int age = 20; double price = 19.99; String name = "Alex"; -

Loops (for, while, do while): Loops repeat code until a condition is met. For example:

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i++) { System.out.println("Count: " + i); }This repeatedly prints “Count: “ and the value of

i. Butistarts at 1 and increases by 1 at each iteration of the loop. The loop only runs as long asiis <= 5, so it prints:Count: 1 Count: 2 Count: 3 Count: 4 Count: 5 -

Conditionals (if else, switch): Make decisions, using if or switch statements. For example:

int score = 85; if (score >= 90) { System.out.println("A"); } else if (score >= 80) { System.out.println("B"); } else { System.out.println("C or below"); }scoreis 85, so it is not >= 90, but it is >= 80. This program should print B -

Arrays: Store multiple values together, in one or two dimensions (like a list or a table).

int[] numbers = {10, 20, 30, 40}; System.out.println(numbers[0]); // prints 10 System.out.println(numbers[3]); // prints 40

-

- Java Fundamentals:

-

Statically typed: Java requires you to specify what kind of data you’re using. That’s why you see keywords like

int,double, orStringbefore a variable name. These are called data types.int x = 5; double y = 2.5; System.out.println(x + y); // Works fine -

Logical Operators (

&&,&,|,||): These control how conditions are checked.int a = 10, b = 0; // Short-circuit: stops early if first part is false if (b != 0 && (a / b) > 2) { System.out.println("Won’t reach here"); } // Non-short-circuit: always checks both sides -> will cause error if (b != 0 & (a / b) > 2) { System.out.println("This will crash!"); }

-

-

Exception Handling: Exception Handling is a way to prepare for possible errors so your program can deal with them gracefully instead of stopping completely. If you don’t handle them, your program will crash.

import java.io.*; public class Main { public static void main(String[] args) { try { FileReader file = new FileReader("data.txt"); } catch (FileNotFoundException e) { System.out.println("File not found!"); } catch (IOException e) { System.out.println("Input/output error occurred."); } } }

Lecture 4: Basic Search and Sorting Algorithms

- Algorithms are step-by-step process to solve a problem or accomplish a task. For example, my “go to school” algorithm has the steps:

- Go to bus stop

- While waiting, open the Teams app to reply to messages

-

Every 1 minute, heads up to see if bus is coming

a/ If bus comes: put my phone a way and hop on bus

b/ If bus doesn’t come: continue replying to messages until bus comes.

- Stay on bus until arrival at bus stop opposite school.

(you might already notice that this algorithm has some loops and conditionals)

- Search and sort are classic example of problems that need to be solved with efficient algorithms. Imagine you are in a huge library with millions of shelves. How would you search your favorite books? Or, as the librarian, how would you sort the books in alphabetical order?

- In practice, the best search and sort algorithms have been well-known, so it’s unlikely that we will discover a better one in this class. But, search and sort are very good examples to teach about complexity and algorithm analysis.

- Complexity: Why analyze algorithms at all? **Turns out, there are a few different ways to search for your favorite in a sea of books, but as you will see, some of them are more efficient and takes less processing steps than others. We call this the “computational complexity” of the algorithm, denoted by O(…). This is called big-O notation. **Big O notation is a special language to tell us how fast or slow an algorithm grows as the input becomes larger.

- When you devise a new algorithm, you can always analyze its complexity. This will tell how efficient (relatively), and how good, your algorithm is. Programmers typically do their best to come up with as efficient algorithms as possible.

- Search algorithms:

- Sequential Search (Linear Search): This method checks elements one by one until a match is found; applicable to unordered lists. If you have

nbooks, this algorithm, on average, will takensteps. We say it has a complexity of O(n) (reads: O of n) in the average case. - Binary Search: This technique requires a sorted array and works by repeatedly dividing the search interval in half. This approach yields an efficient time complexity of O(log n), which is significantly better than O(n) for large datasets.

- Sequential Search (Linear Search): This method checks elements one by one until a match is found; applicable to unordered lists. If you have

- Sort algorithms:

-

Bubble Sort: Bubble Sort works by repeatedly comparing and swapping neighboring elements if they’re in the wrong order.

Example: Imagine you have numbers: [5, 2, 4, 1].

- Compare 5 and 2 → swap → [2, 5, 4, 1]

- Compare 5 and 4 → swap → [2, 4, 5, 1]

-

Compare 5 and 1 → swap → [2, 4, 1, 5]

After one round, the largest number “bubbles up” to the end (5). You repeat this process until the whole list is sorted.

This algorithm is incredibly inefficient because it compares and swaps numbers lots and lots of time. If we analyze its complexity, it comes to O(n^2).

-

Selection Sort: Selection Sort works by repeatedly finding the smallest number and moving it to the front.

Example: With [5, 2, 4, 1]:

- Find smallest (1) → move it to front → [1, 2, 4, 5]

-

Find next smallest (2) → already in place → [1, 2, 4, 5]

Continue until all are sorted.

Even though it swaps less often than Bubble Sort, it still makes many comparisons to find the smallest element each time — so it’s also inefficient for large lists. Its time complexity is also O(n^2).

-

In the lectures, we stop here. In the next lessons after midterm, we will learn about efficient algorithms that have complexity of O(n * log n), which is much faster than O(n^2).

If you have trouble imagining the algorithms works step by step, you can check out the animations here:

- Linear vs Binary Search: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gJvhiR7Yi6Q

- Bubble Sort: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9I2oOAr2okY

- Selection Sort: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iccmrk2ZWoc

Thanks for reaching the end. You might have noticed that I’m already applying some CT principles in writing this recap:

- Decomposition: breaking hundreds of slides down to digestible concepts

- Abstraction: explaining each concept briefly without going into details

- Pattern recognition: understand non-CS students usually prefer and tailor the tone & content accordingly.

It goes to show how CT can be applied it most problems, even when you don’t recognize it.

Revising some important programming concepts (Module 3)

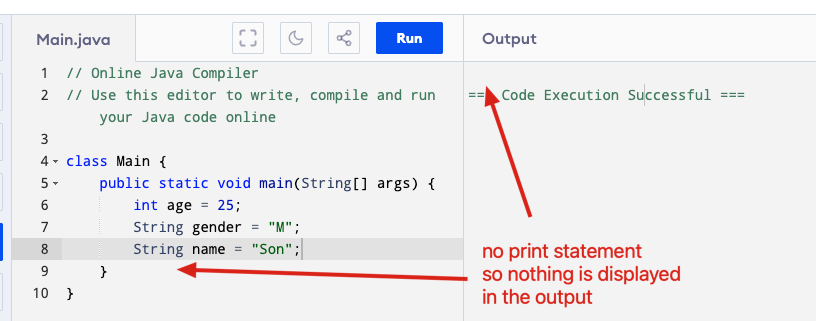

1. Variables: The Data Storage Containers

Think of a variable as a labeled box . You use these boxes to store data that the program needs to remember and use later.

The Key Idea: A variable has three parts:

- Type: What kind of data goes in the box? (e.g., a whole number, a decimal number, a word, etc.)

- Name: The label on the box so you can find it later (e.g.,

score,userName,isRaining). - Value: The actual data currently inside the box.

Take these 2 lines of code for example.

(The eagle eyes among you might notice I’m not following Java convention of naming things, in which I should name the variable firstName. first_name is actually Python convention, which is what I’m more used to).

int age = 25;

String first_name = "Son";

The first line is for a variable named “age”, its data type is “int” (which is Java’s symbol for integers), and its value is the integer 25.

The second line is for variable named “first_name”, its data type is “String” (which is Java’s symbol for texts), and its Value is “Son”.

We can make Java display the variable’s value on the screen using the “print” or “println” function (its full name in Java is System.out.println). From now on, we’ll use the word print (or sometimes, just “output”) to talk about displaying things on screen.

2. Conditions

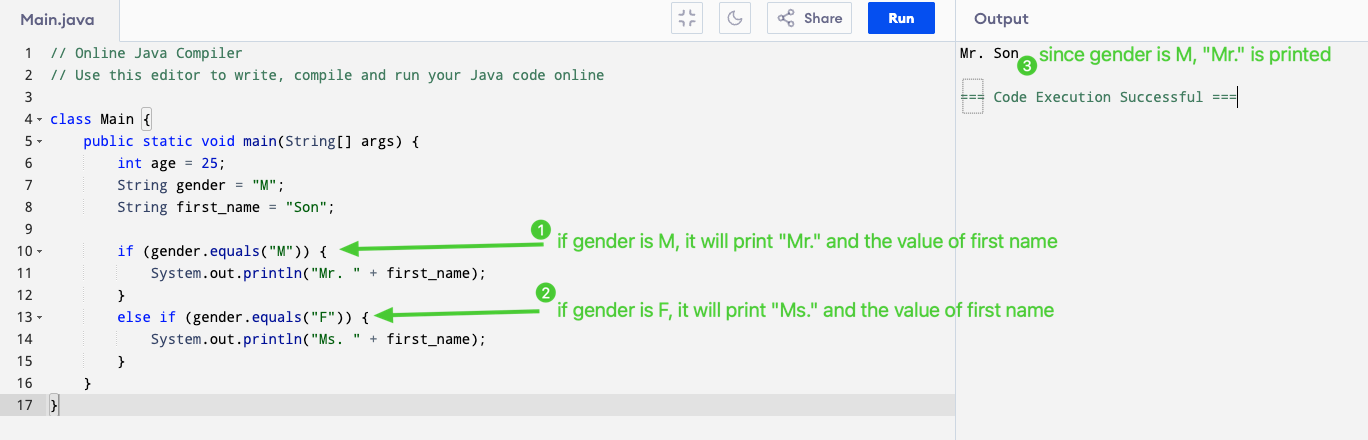

A. The if/else Statement

This is how a computer chooses which path to follow based on a specific condition. It’s the most basic form of intelligence in a program.

The Key Idea: The computer checks a statement that is either true or false.

-

if: “If the condition is true, do the first set of instructions.” -

else: “Otherwise (if the condition is false), do the second set of instructions.”

Example:

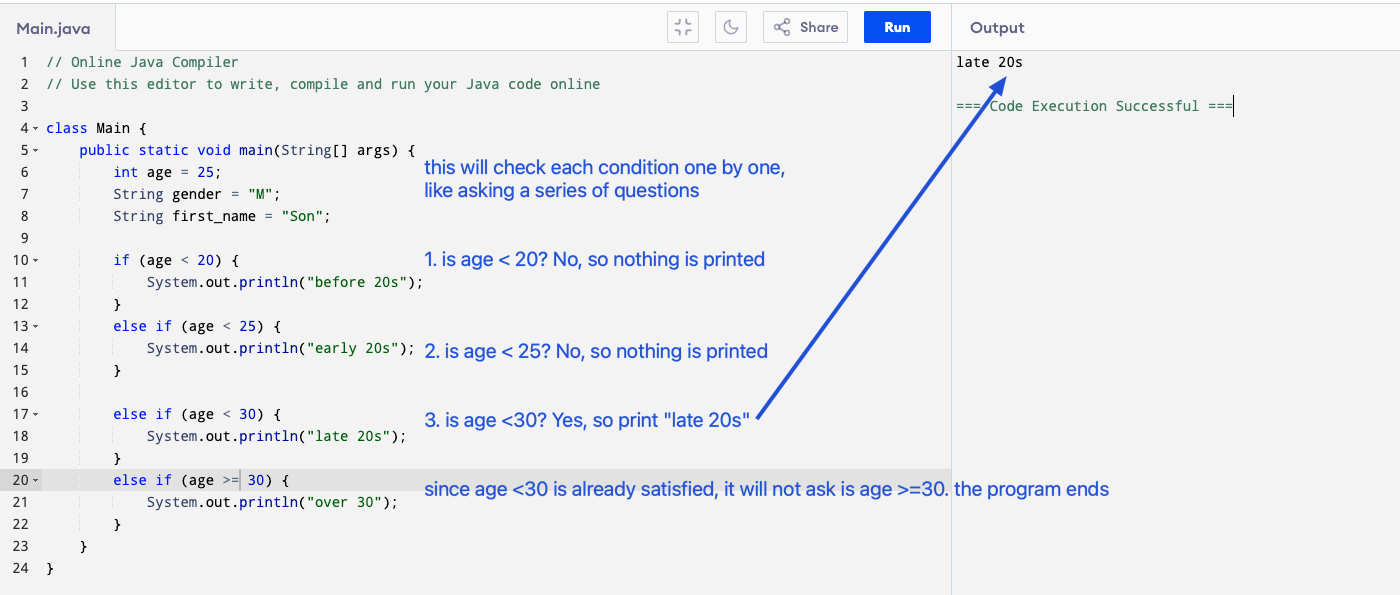

Another example where we need to check more than one or two conditions. Imagine this is like asking a series of questions until one is “Yes”.

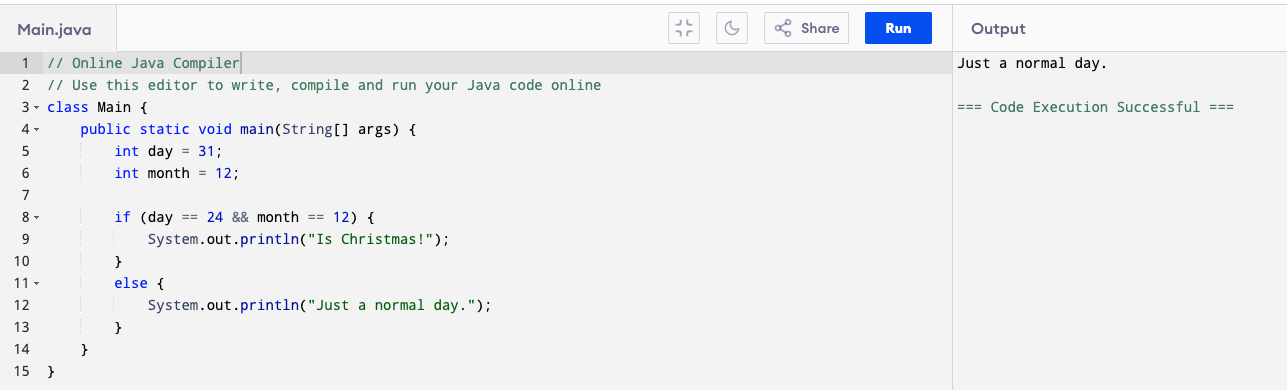

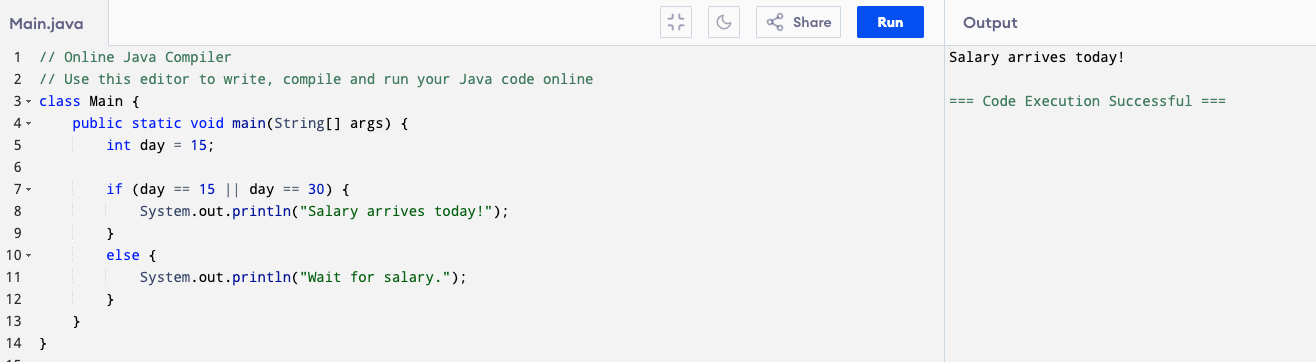

You can also checks if both conditions are true at the same time using the && (and) sign. For example day == 24 && month == 12 will print “Is Christmas!” if day is 24 AND month is 12. Because month is 12 but day is 31, it prints “Just a normal day.”

You should also know || (or) sign. For example day == 15 || day == 30 will print “Salary arrives today!” if day is 15 or day is 30.

Note on Short-Circuit Evaluation

When Java checks conditions joined by && (AND) or || (OR), it stops evaluating as soon as the final result is known.

This is called short-circuit evaluation.

if (x != 0 && 10 / x > 1) {

System.out.println("Safe division");

}

- Java first checks x != 0.

-

If that’s false, it won’t check 10 / x > 1,

because the whole && expression can never be true.

✅ This prevents errors like dividing by zero.

For || (OR), Java also short-circuits:

if (day == 1 || day == 15) {

System.out.println("Payday!");

}

- If the first condition (day == 1) is already true, Java skips checking the second one (day == 15), because the result is already true.

Java also has non–short-circuit versions:

- & → checks both sides even if the first is false

-

→ checks both sides even if the first is true

if (x != 0 & 10 / x > 1) {

System.out.println("This may cause an error!");

}

Even if x != 0 is false, Java will still evaluate 10 / x > 1, 💥 causing a division by zero error.

So always use:

-

&&and||for logic (safe and common) -

&and|for bitwise operations, not normal conditions.

Let’s practice, depending on what today is when you read this, what will this print?

if (today.equals("7/11")) {

System.out.println("Tomorrow is my birthday!");

}

else if (today.equals("8/11")) {

System.out.println("Today is my birthday!");

}

else if (today.equals("9/11")) {

System.out.println("Yesterday was my birthday!");

}

B. The switch statement

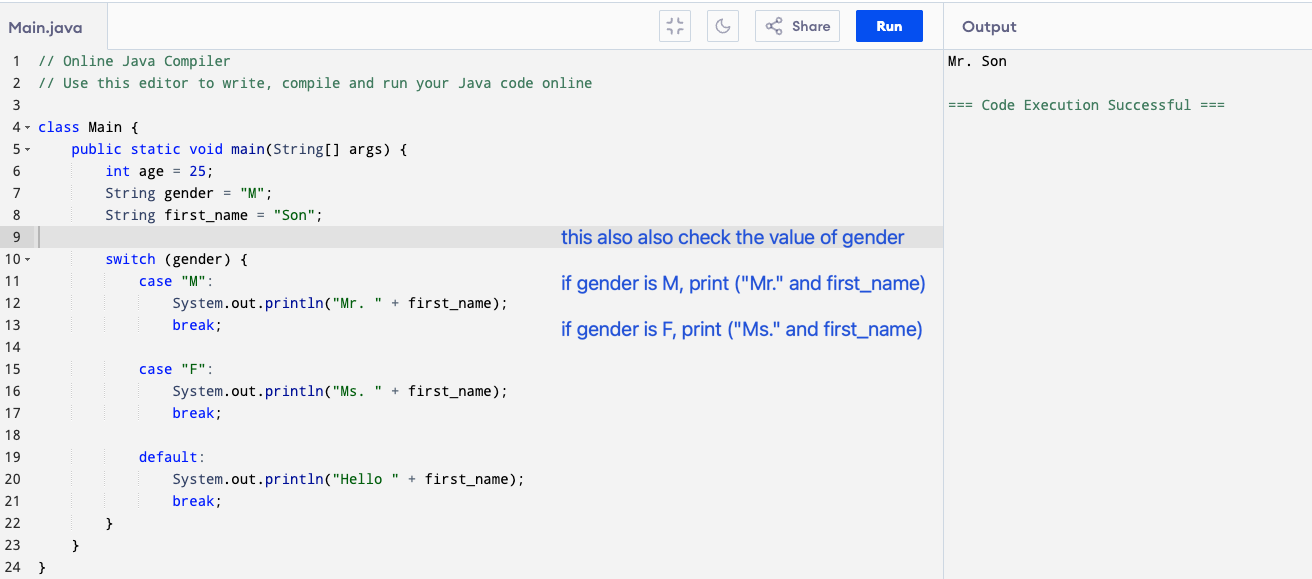

In class, we also learn about the switch statement to write conditionals:

- switch (gender) → checks the value stored in gender.

- Each case compares it to a possible value:

- If it’s “M” → prints “Mr.” and

first_name. - If it’s “F” → prints “Ms.” and

first_name. - If it doesn’t match any case → the default runs.

- If it’s “M” → prints “Mr.” and

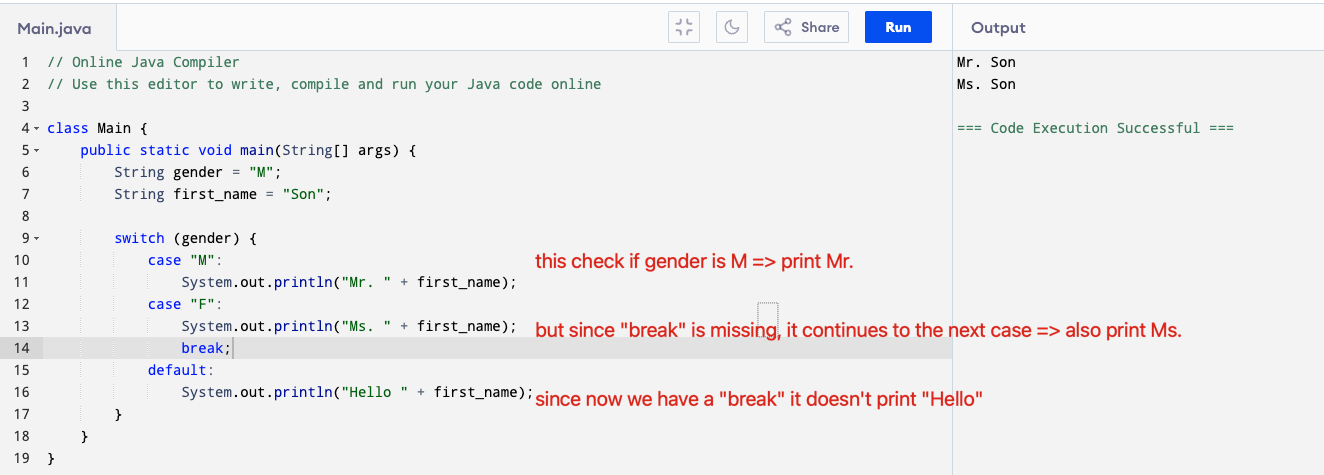

- break; stops the program from continuing to the next case.

The break statement and needs to be included in every case because it stops the switch from falling through to the next case.

3. Loops: The Repetition Machines

If you need the computer to perform the same task 100 times, you don’t want to write the code 100 times. That’s where loops come in. Loops allow you to repeat a block of code until a certain condition is met.

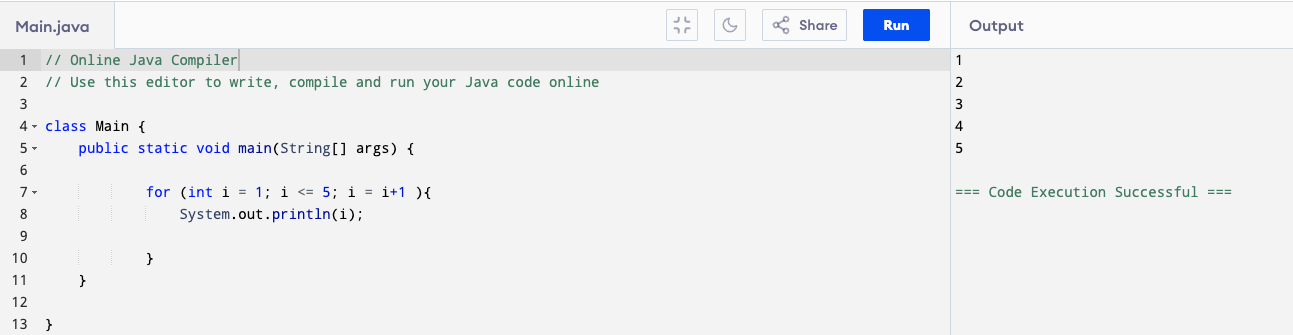

A. The for Loop (The Counter)

The for loop is typically used when you know exactly how many times you want the code to repeat.

The three parts of a for loop:

- Start: Where to begin the counter (

int i = 0;). - Stop Condition: When to stop looping (

i < 5;). - Change: How to update the counter each time (

i = i + 1means add 1).

Example: Counting from 1 to 5.

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i = i + 1) {

System.out.println(i);

}

Here’s what happens when we write a for loop:

- The loop starts with i = 1.

- It checks if i <= 5.

- If true, it runs the body of the loop.

- Inside the loop, this line runs:

System.out.println(i);

It prints the current value of i.

- After printing, the loop increases i by 1.

- It repeats the process until i becomes greater than or equal to 5.

When tracking what a loop does, it helps to write down how things change after each loop run (we call that an “iteration”):

| Iteration | Value of i | Printed output | is i < 5? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 1 | 1 | yes, print i |

| 2nd | 2 | 2 | yes, print i |

| 3rd | 3 | 3 | yes, print i |

| 4th | 4 | 4 | yes, print i |

| 5th | 5 | 5 | yes, print i |

| 6th | 6 | 6 | no, don’t print i. |

| stop the loop. |

So that’s why in the output, you see it prints all the values 1 2 3 4 5, not just 5 or just 1.

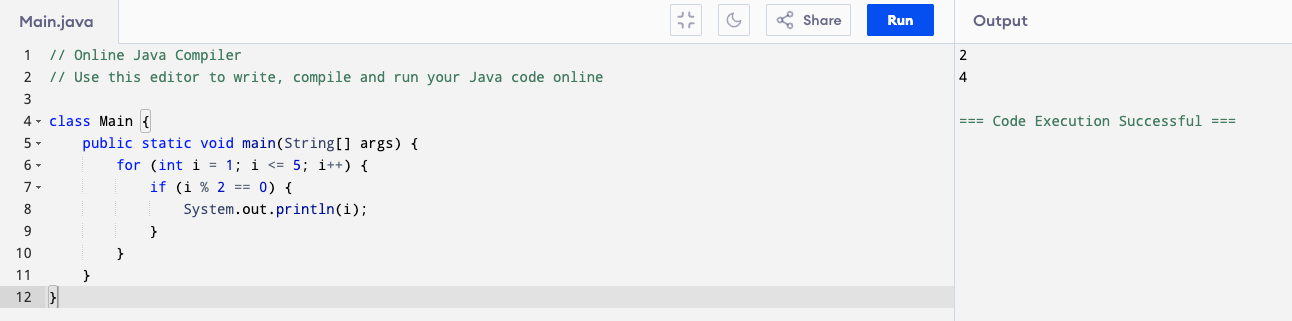

We can do more things by adding an if else statement within a for loop. For example, this code will check if i is an even number. If yes, it will print i. If no, it will not print anything. So that’s why only 2 and 4 are printed, not 1, 3, 5.

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i = i + 1) {

if (i % 2 == 0) {

System.out.println(i);

}

By the way, this sign % is not a percentage, it’s the “modulus” operator. a % b gives the remainder when a is divided by b (Vietnamese: lấy phần dư của phép chia). For example:

| Expression | Meaning | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 5 % 2 | 5 divided by 2 leaves remainder 1 | |

| (5 chia 2 dư 1) | 1 | |

| 10 % 3 | 10 divided by 3 leaves remainder 1 | 1 |

| 15 % 4 | 15 divided by 4 leaves remainder 3 | 3 |

| 7 % 5 | 7 divided by 5 leaves remainder 2 | 2 |

If a number’s remainder when divided by 2 is 0, it’s an even number. If the remainder is 1, it’s an odd number (Vietnamese: Nếu một số chia 2 dư 0 thì số đó là số chẵn, nếu dư 1 là số lẻ).

So, can you work out what this code will print?

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

for (int i = 10; i <= 15; i++) {

if (i % 3 == 0 && i % 5 == 0) {

System.out.println("FizzBuzz");

}

else if (i % 3 == 0) {

System.out.println("Fizz");

}

else if (i % 5 == 0) {

System.out.println("Buzz");

}

else {

System.out.println(i);

}

}

}

}

If you’re stuck, open this website and run the code: https://www.programiz.com/java-programming/online-compiler/

B. The while Loop (The Condition Checker)

The while loop is used when you don’t know exactly how many times you need to repeat, but you know that the repetition must continue as long as a certain condition is true.

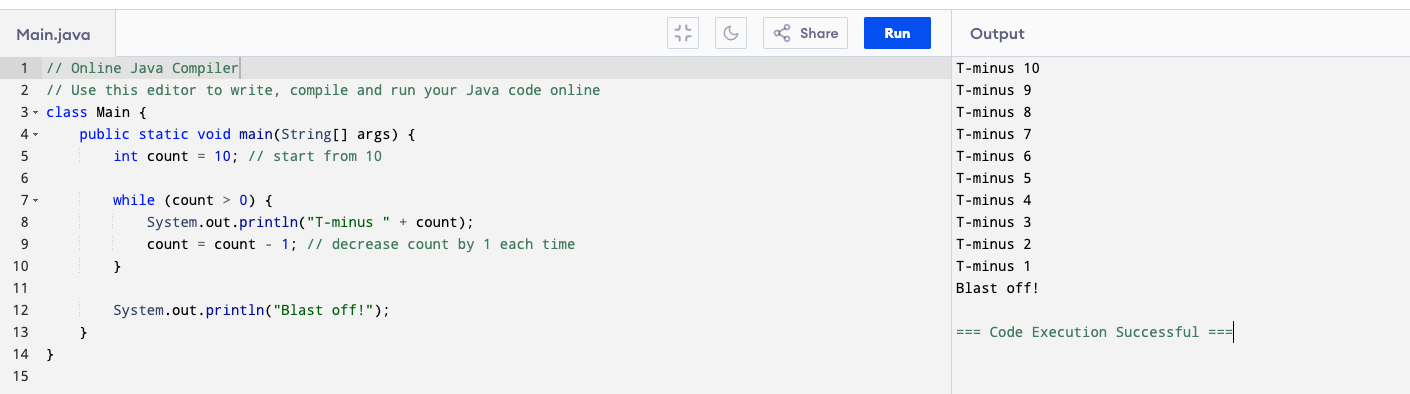

Example: Countdown Program

The program keeps repeating the code inside the loop as long as the count is greater than 0. Once it hits 0, the condition becomes false, and the loop stops immediately. That’s why you don’t see it print T-minus 0.

Step by step

- We start with count = 10.

- The loop condition is count > 0, so it runs as long as count is still positive.

- Each time:

- It prints the countdown number.

- Then subtracts 1 from count (

count = count - 1).

- When count reaches 0, the condition becomes false, and the loop stops.

- After the loop, we print “Blast off!”.

4. Arrays and Indexes

An array is a special type of variable that holds a collection of values. All the data inside an array must be the same type (e.g., all whole numbers, or all names).

For example:

int[] numbers = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

- the signs

[]tells you this will be an array -

intsignals this is an array of integers -

{10, 20, 30, 40, 50}are the elements of this array.

You can get the value of an element in the array by accessing its position (the position is called the “index”). In programming, the position starts from 0, so 0 will give the 1st element, 1 will give the 2nd,… and 4 will get the 5th.

For example:

int[] numbers = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

System.out.println(numbers[1]); // will print 20

System.out.println(numbers[3]); // will print 40

System.out.println(numbers[5]); // will get error because indexes are from 0 to 4

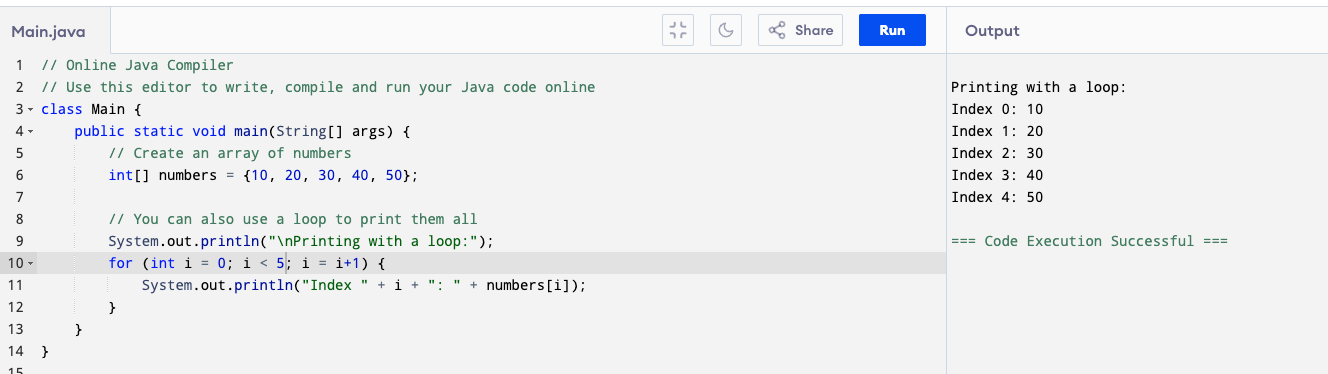

You can loop through the array by looping through its elements like this:

Remember from the for loop example:

-

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i = i+1)will give i from 0 to 4 - so

numbers[i]will in turn out to benumbers[0](10) ,numbers[1](20), tonumbers[4](50) - That’s why it prints each element in the array.

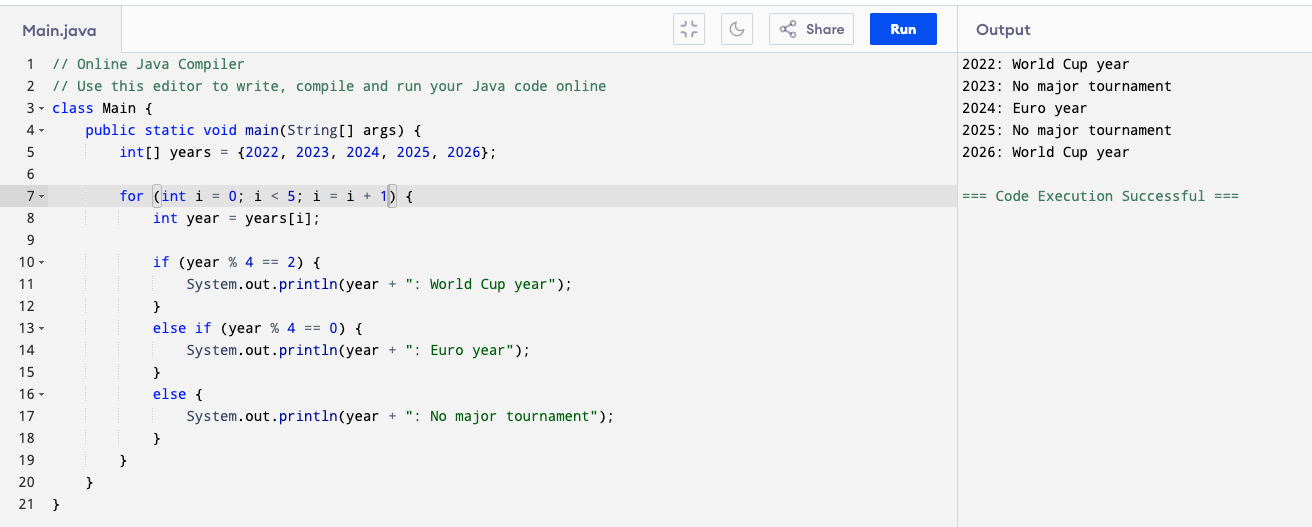

We can combine the knowledge from loop, conditions, and array to understand this example:

- The loop goes through each element in the array (from index 0 to 4) and check.

- year % 4 == 2 → means the remainder is 2 when divided by 4 (like 2022, 2026, 2030, …).

- These are World Cup years (every 4 years, offset by 2).

- year % 4 == 0 → means the remainder is 0 (like 2020, 2024, 2028, …).

- These are Euro years (every 4 years).

- Otherwise → no major tournament.

Now that we know some programming concepts, can you try to write the output to this program?

class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] numbers = {12, 7, 25, 40, 18};

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.length; i++) {

int n = numbers[i];

if (n > 30) {

System.out.println(n + ": Large number");

}

else if (n >= 15 && n <= 30) {

System.out.println(n + ": Medium number");

}

else if (n < 15 && n % 2 == 1) {

System.out.println(n + ": Small odd number");

}

else {

System.out.println(n + ": Small even number");

}

}

}

}

Again, if you are lost, go to https://www.programiz.com/java-programming/online-compiler/ to run this program. Ask TA or ChatGPT to explain this line by line.

Abstract Data Structures: What Are They? (Module 5)

Abstract Data Structures or Abstract Data Types (ADTs) are like special containers or boxes that programmers use to store data. Each ADT has different ways of adding, removing, and accessing an item, hence, they are used to solve different problems. That’s mostly what we’ll need to pay attention to when learning ADT: how data is added, removed or accessed, and which operation is best suited to each ADT.

[A good analogy is the wardrobe. We can hang clothes, which lets us see and pick any item directly, or we can fold them in a pile, which means we typically grab from the top. Similarly, ADTs give programmers various options to store data depending how they want to access it.]

1. Stack (LIFO) and Queue (FIFO)

1a. Stack

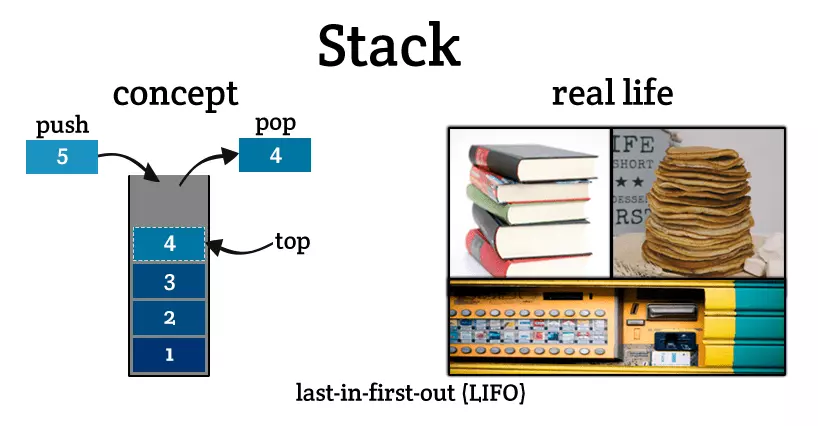

The “stack” is similar to a stack of books. It is created by “pushing” items on top of one another. That is, the way we add data is by simply “pushing” the new item on top of the existing ones. In the picture, we can add book 5 by pushing it on top of book 4.

What about removing data? This data structure designed to easily get the “last” item out. For example, in this picture, we want to easily get book 4. This is great for implementing undo functions: your most recent action is undone first, then the one before it, and so on (think Ctrl+Z).

What happens if we want to access book 1? A stack doesn’t allow you to get book 1 directly, instead, you have to “pop” (pop is the programming equivalent of “remove”) books 4, 3, 2 before you can get to book 1.

Some other applications of stacks are:

- Math for Computers:

- Computers don’t calculate $3 + 4$ like humans. They often use a stack to solve complex equations like $A \cdot B + C / D$.

- They push numbers onto the stack and pop them when they see an operator (like $+$ or $*$).

- Solving Mazes (Backtracking):

- Imagine a robot in a maze. Every time it takes a step, it pushes its location onto a stack.

- If it hits a dead end, it pops the stack to go back to the last intersection and try a different path. This is called Backtracking.

1b. Queue

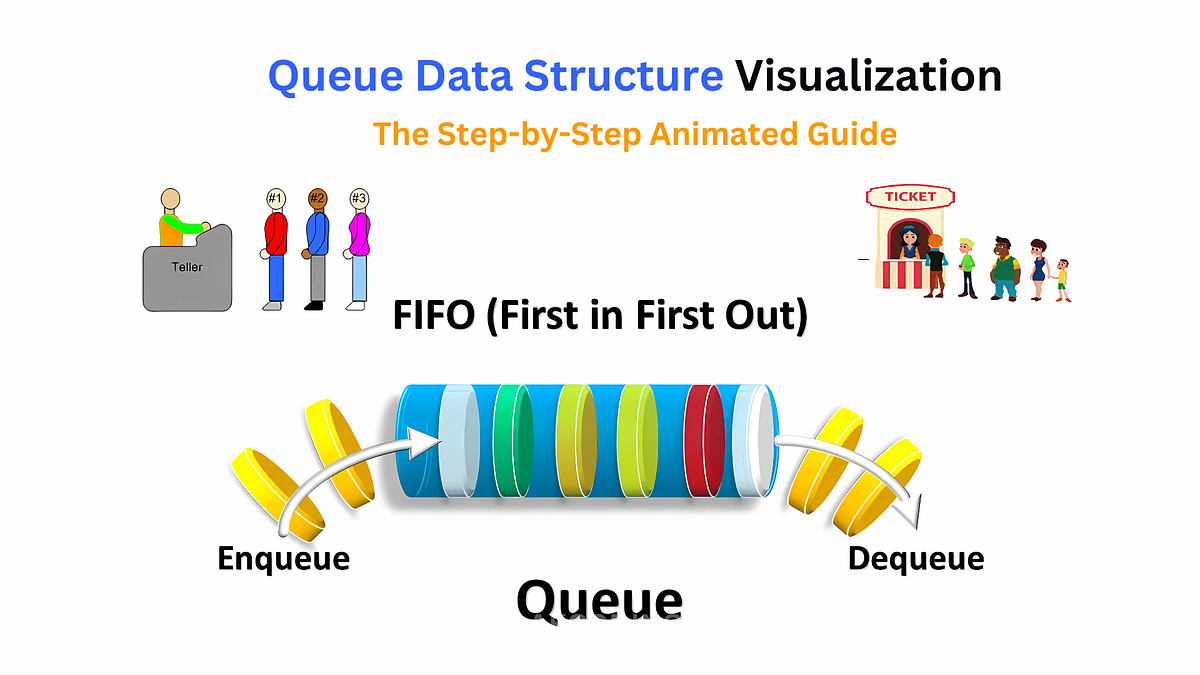

Meanwhile, the “queue” is designed to access the “first” item. Imagine a literal queue in a coffee shop: new items are added at the back of the line.

A queue allows programmers to directly access the item at the “front” (i.e., the first item that was added). Imagine you have customers coming to you in this order: #1, #2, #3.

In a “queue”, #1 will be accessed first, then #2 and #3. There is no way for customer #3 to be served first: a queue will always process #1, then #2 before getting to #3. This is great for implementing order systems (first customers get served first).

[The correct term for “adding” is “enqueue”, and “removing” is “dequeue”]

2. Binary Search Tree (BST)

2a. What’s a BST and why is it called “search”?

Think of something like a family tree or a company’s chart:

Grandparent

├── Parent A

│ ├── Child 1

│ ├── Child 2

│ └── Child 3

└── Parent B

├── Child 4

└── Child 5

Technically it’s a structure with multiple levels, where one item in the lower level is the “child” of exactly one item above it – except the item at the highest level which doesn’t have any “parent”. The highest item is called the “root”.

A “binary tree” is like that, with one special rule: each item has at most 2 children.

A

/ \

B C

/ \

D E

A “binary search tree” is a binary tree, but with another special organizing rule: smaller items go left, bigger items go right.

10

/ \

5 15

/ \

2 7

Suppose the top number is 10:

- Numbers smaller than 10 go to the left

- Numbers bigger than 10 go to the right

So:

- 5 is left of 10 (smaller)

- 15 is right of 10 (bigger)

- 2 is left of 5

- 7 is right of 5

Why is it called a “search” tree? Because this setup makes finding things fast. If you’re looking for 7:

- Start at 10 → 7 is smaller → go left

- At 5 → 7 is bigger → go right

- Found it

At each step, you ignore half the remaining options.

2b. Some terminologies

We describe a tree and its node in terms of its levels, depth and height:

- A node has a level (start counting from 0). In the previous example “10” is at level 0, “5” and “15” are level 1 and so on.

- A node’s depth is the same as its level. So node “7” has depth 2.

- A tree’s height is its maximum depth. In the previous example, the max depth is 2, so we say the tree has height 2.

2c. Insertion

We know that a BST is a tree where a parent has at most 2 children, and in a tree, smaller items are always to the left. Let’s learn how insertion is performed, such that those rules are maintained.

Inserting an item is very easy: you go from the root node, and at each time node you ask “should this go left or right?” until you find an empty spot, then you place it there.

Example: Let’s insert 6 to this tree:

8

/ \

3 10

- Compare with 8

- 6 is smaller → go left

- Compare with 3

- 6 is bigger → go right

- Right side of 3 is empty → insert here

8

/ \

3 10

\

6

2d. Deletion

Deleting is a bit tricky, because if we remove a parent node, it will leave a “gap”.

For example: Removing 3 from the previous tree would make leave a gap

8

/ \

3 10

\

6

8

/ \

... 10

\

6

This gap is not allowed in a tree. So we need some re-arranging such that no gap exists. Let’s deal with each case one by one.

Case 1: Deleting a leaf (no children) This is the easiest. For example, to delete 6:

8

/ \

3 10

\

6

8

/ \

3 10

Case 2: Deleting a node with one child

You “skip over” the deleted item. The child takes the place of the deleted node.

For example: To delete 3, move its child (6) to take its place:

8

/ \

3 10

\

6

8

/ \

6 10

Case 3: Deleting a node with two children (hardest)

You replace it with a nearby value that keeps the BST rule.

Either:

- the largest value on the left [a predecessor], or

- the smallest value on the right [a successor]

(you replace a node with one of its grandchildren or grand-grandchildren and so on, not only its immediate children)

For example: To delete 8, we can either choose the smallest item on the right of 8, which is 10:

8

/ \

3 10

\

6

10

/

3

\

6

or, we can choose the largest value that is smaller than 8, which is 6:

8

/ \

3 10

\

6

6

/ \

3 10

Either answer is acceptable.

In this case, moving 6 or 10 to replace 8 is easy since they do not have a child. A more tricky operation would be when the replacement has children.

Take this tree, let’s say we want to remove 8:

8

/ \

4 12

/ \

10 15

\

11

Suppose we want the take the successor (smallest item on the right side), which is 10.

First, we copy 10 to replace 8 (notice that the original 10 is still there). Then, delete 10 and replace it with its successor, which is 11 in this case. [Since we 10 itself is the smallest value on the right hand of 8, 10 cannot have a predecessor.]

// copy 10 to replace 8

10

/ \

4 12

/ \

10 15

\

11

2e. Skewed/ Balanced Trees

// promote 11 into 10's place

10

/ \

4 12

/ \

11 15

Depending on the order in which elements are inserted, the BST will look different. That is, even though the elements are the same, the order in which they are inserted will determine what the tree look like.

For example, with these same items: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

If we insert them in this order: 3 → 2 → 1 → 4 → 5, we’ll get this tree:

3

/ \

2 4

/ \

1 5

However, if we get unlucky and we insert them in this order: 1 → 2 → 3 → 4 → 5 (or the reverse), we’ll get this ridiculous looking tree:

1

\

2

\

3

\

4

\

5

5

/

4

/

3

/

2

/

1

This is an example of a skewed tree. A skewed tree is very unfortunate, because it makes search slow, which defeats the purpose of a BST.

Let’s say we want to find the item “5”:

- In the balanced tree:

- Compare 5 with 3 → Larger → Go Right ⇒ by going right here, you have effectively ignored half of the tree

- → Compare 5 with 4 → Larger → Go right

- → Compare 5 with 5 → Found.

- In the skewed tree:

- Compare 5 with 1 → Larger → Go right

- Compare 5 with 2 → Larger → Go right

- … you have to look through every element before you find 5.

We say that in a balanced BST, the average time to search is O(log N) (fast), whereas in a skewed tree it’s O(N) (slow).

3. Binary Heap

3a. Binary Heap is a Complete Binary Tree

It is a complete binary tree, meaning:

- all levels are filled (except possibly the last level)

-

nodes in the last level are filled from left to right, with no gaps

Example: Possible positions at the last level: [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ]

-

[ X ] [ X ] [ ] [ ]✅ Valid -

[ X ] [ X ] [ X ] [ ]✅ Valid -

[ X ] [ ] [ X ] [ ]❌ Invalid (gap)

-

For example, this is a complete tree:

A

/ \

B C

/ \ /

D E F

So what isn’t a complete binary tree? These:

// gap on the left of E

A

/ \

B C

\ /

E F

// hole in the last level

A

/ \

B C

/ \

D F

3b. Binary Heap is a Special Binary Tree

A binary heap is a complete binary tree that satisfies the heap property:

- Min-heap: every parent ≤ its children

- Max-heap: every parent ≥ its children

For example, Let’s use: [10, 5, 3, 2, 4, 8]

Example of a Max-heap:

Rule: Every parent ≥ its children

→ The largest value is always at the root

10

/ \

5 8

/ \ /

2 4 3

Check:

- 10 ≥ 5, 8 ✔

- 5 ≥ 2, 4 ✔

- 8 ≥ 3 ✔

What about a Min-heap?

Rule: Every parent ≤ its children

→ The smallest value is always at the root

2

/ \

4 3

/ \ /

10 5 8

Check:

- 2 ≤ 4, 3 ✔

- 4 ≤ 10, 5 ✔

- 3 ≤ 8 ✔

Note that there can be many different heaps for the same set of values. For example, if you check this max-heap, it is valid:

10

/ \

8 5

/ \ /

2 4 3

3c. Insertion

The rule for insertion in a max-heap is:

- Insert the new value at the next available position (leftmost on last level)

- Bubble up (swap with parent) until heap property holds

And for min-heap it’s similar:

- Insert at next available spot

- Bubble up if smaller than parent

After inserting, check the new node against its parent to see if the max-/min-heap property is satisfied (example below).

Let’s try to create a max-heap by inserting items one by one. Insert: 10 → 5 → 8 → 2 → 4

// Insert 10

10

// Insert 5

10

/

5

// 5 ≤ 10 → OK

// Insert 8

10

/ \

5 8

// 8 ≤ 10 → OK

// Insert 2

10

/ \

5 8

/

2

// 2 ≤ 5 → OK

// Insert 4

10

/ \

5 8

/ \

2 4

// 4 ≤ 5 → OK

Now, what if we want to insert 9 into this tree? If we simply add 9 to the next possible position, it will look like this:

10

/ \

5 8

/ \ /

2 4 9

But this doesn’t satisfy the max-heap property (every parent ≥ its children), so we need to “bubble up”, meaning to swap 9 with its parent until the rule is satisfied:

// bubble up (9 > 8) -> swap

10

/ \

5 9

/ \ /

2 4 8

Now check again, 9 ≤ 10 is satisfied → stop.

3d. Deletion

What happens we where want to delete from a heap? When deleting from a heap, what we most often do is removing the root node (it’ll make sense later).

So how to remove the root node while keeping the heap property?

Let’s take this max-heap:

10

/ \

5 9

/ \ /

2 4 8

We remove the root node, and replace it with the last node (for a max-heap: the rightmost, bottom node), which is 8

8

/ \

5 9

/ \

2 4

But this doesn’t satisfy the parent ≥ children rule of max-heap (because 8 is smaller than 9).

What we have to do is “bubble down”, meaning to compare 8 with its child and swap. When bubbling down in a max-heap, always swap with the larger child to maintain the heap property

// larger child = 9

// 8 < 9 → violation → swap

9

/ \

5 8

/ \

2 4

We continue to check for 8’s children. Now it has none, so no more check. The max-heap property is now satisfied and all parents ≥ children.

The deletion is now complete.

3e. Insertion & Deletion for Min-Heap

Sections 3c and 3d have shown how insertion and deletion works for max-Heap. It’s the same for a min-heap. Let’s take an example.

Starting from this valid min-heap.

2

/ \

4 3

/ \

10 5

Here’s the steps for inserting 1:

// Insert at next available position

// (next spot = left child of 3)

2

/ \

4 3

/ \ /

10 5 1

// Bubble up: Compare 1 with parent 3

// 1 < 3 → swap

2

/ \

4 1

/ \ /

10 5 3

// Bubble up again: Compare 1 with parent 2

// 1 < 2 → swap

1

/ \

4 2

/ \ /

10 5 3

// Stop (at root).

Now, how to remove 1?

// Take the last node (3)

// move it to the root.

3

/ \

4 2

/ \

10 5

// Bubble down: Compare 3 with its child

// 3 > 2 → swap

2

/ \

4 3

/ \

10 5

// Node 3 has no children

// Heap property holds → stop

3f. Priority Queue

A priority queue is an ADT kinda like a queue, except each item has a “priority”. So we can access and delete items based on its priority score, not just the order it was inserted. This is great for tasks with priority, such as task scheduling on systems (i.e., some tasks need to be executed before others).

Binary heap is commonly used to implement priority queues. Due to the min-/max-heap property we talked about earlier, the heap already has the smallest or largest item at the top, so to find the high priority task, we only need to look at the root node.

Let’s take this example: Suppose tasks have priorities (smaller number = more urgent):

| Task | Priority |

|---|---|

| A | 5 |

| B | 1 |

| C | 3 |

Stored in a min-heap:

B(1)

/ \

A(5) C(3)

- Remove → B (priority 1)

- Next remove → C

- Then → A

Exactly what a priority queue promises.

References

https://viblo.asia/p/stack-va-queue-thi-ung-dung-duoc-gi-vao-du-an-thuc-te-r1QLxB8o4Aw

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/dsa/introduction-to-stack-data-structure-and-algorithm-tutorials/

Revision on Recursion (Module 6)

This tutorial introduces recursive thinking in a calm, intuitive way. We will focus on how to think recursively, not just how to write code.

We will cover:

- What recursion is

- Base case and recursive case

- Factorial

- Fibonacci numbers

- The stepping (stairs) problem

1. What Is Recursion?

Recursion means:

Solving a problem by breaking it into

smaller versions of the same problem

Instead of solving everything at once, you say:

- “If I can solve a smaller version, I can solve the whole thing.”

Everyday Analogy

Imagine you want to know how many pages are in a book:

- You check the first page (1)

- Then ask: “How many pages are in the rest of the book?”

- That question repeats until no pages are left

That is recursive thinking.

2. Two Rules of Recursion (Very Important)

Every recursive solution must have both:

1️⃣ Base Case (Stopping Rule)

- The simplest version of the problem

- Stops the recursion

2️⃣ Recursive Case (Self-Call)

- Breaks the problem into a smaller version

- Calls itself

If you forget the base case → infinite loop ❌

3. Factorial (Classic Example)

What Is Factorial?

Factorial of a number n (written as n!) means:

5! = 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1

Recursive Thinking for Factorial

Instead of memorizing the formula, think like this:

“To compute factorial of n, multiply n by factorial of (n − 1).”

Base Case

1! = 1

This stops the recursion.

Recursive Breakdown (Step by Step)

5! = 5 × 4!

4! = 4 × 3!

3! = 3 × 2!

2! = 2 × 1!

1! = 1 ← base case

Now resolve from bottom up:

1! = 1

2! = 2

3! = 6

4! = 24

5! = 120

Visualization

fact(5)

└─ 5 × fact(4)

└─ 4 × fact(3)

└─ 3 × fact(2)

└─ 2 × fact(1)

└─ 1

4. Fibonacci Numbers

Problem Description

The Fibonacci sequence:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, ...

Rule:

- Each number is the sum of the previous two

Recursive Thinking

“To get Fibonacci(n), add Fibonacci(n − 1) and Fibonacci(n − 2).”

Base Cases

Fib(0) = 0

Fib(1) = 1

Example: Fib(4)

Fib(4)

= Fib(3) + Fib(2)

Fib(3)

= Fib(2) + Fib(1)

Fib(2)

= Fib(1) + Fib(0)

Substitute values:

Fib(2) = 1

Fib(3) = 2

Fib(4) = 3

5. The Stepping (Stairs) Problem

Problem Description

You are climbing stairs.

- You can take 1 step or 2 steps at a time

- Given that there are total n steps. How many different ways are there to reach the top?

Small Examples

1 step → 1 way

2 steps → 2 ways (1+1, 2)

3 steps → ?

Recursive Thinking

To reach step n, you must come from:

- Step n − 1 (take 1 step)

- Step n − 2 (take 2 steps)

So:

ways(n) = ways(n − 1) + ways(n − 2)

Base Cases

ways(1) = 1

ways(2) = 2

Example: 4 Steps

ways(4)

= ways(3) + ways(2)

= 3 + 2

= 5

Possible ways:

1+1+1+1

1+1+2

1+2+1

2+1+1

2+2

Key Insight

The stepping problem has the same structure as Fibonacci.

Different story — same recursion pattern.

Revision on Algorithms (Module 7)

This tutorial gives you a gentle, intuitive introduction to algorithms. We will avoid heavy math and focus on ideas, examples, and step-by-step thinking.

We will cover:

- The Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

- Greedy Algorithms

- Dijkstra’s Algorithm

- Minimum Spanning Tree (MST)

Throughout the tutorial, we will use small toy examples so you can clearly see how each algorithm works.

1. What Is an Algorithm?

An algorithm is simply a step-by-step procedure to solve a problem.

Think of a recipe:

- Input: ingredients

- Steps: cooking instructions

- Output: a finished dish

Algorithms work the same way:

- Input: data

- Steps: rules to process the data

- Output: the solution

2. Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

Problem Intuition

Imagine a salesman who:

- Starts from a city

- Must visit every other city exactly once

- Must return to the starting city

- Wants to travel the shortest total distance

This is called the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP).

Using a Distance Matrix

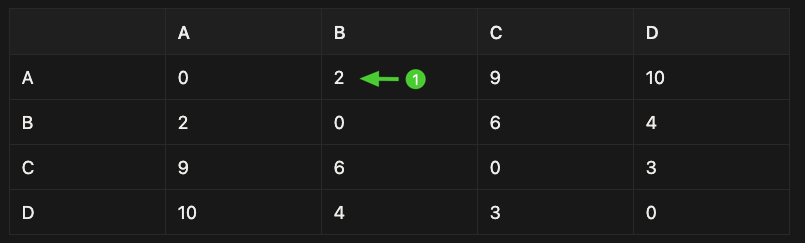

We represent distances using a distance matrix.

Example: 4 cities (A, B, C, D)

| A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 2 | 9 | 10 |

| B | 2 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| C | 9 | 6 | 0 | 3 |

| D | 10 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

- Row = starting city

- Column = destination city

- Value = distance

For example, A is 2 units away from B, 9 away from C and 10 away from D, and so on.

A Toy Example Route

Suppose we try the route:

A → B → D → C → A

Step-by-step distance:

- A → B = 2

- B → D = 4

- D → C = 3

- C → A = 9

Total = 2 + 4 + 3 + 9 = 18

We can compare this with other routes and choose the shortest.

But, how many possible routes can we take? Since we have 4 cities, there are 4! = 24 possible routes to consider. Now consider just 8 cities, that 8! = 40320 combinations. As we scale up the number of destinations, the number of combinations rises quickly and it soon becomes inefficient to consider all the paths.

That’s why we need some smarter algorithms

3. Greedy Algorithms

Core Idea

A greedy algorithm:

- Makes the best choice at the current step

- Does not look far into the future

Think of it as:

“Take what looks best right now.”

Greedy algorithms are:

- Fast

- Simple

- Not always optimal (but often good enough)

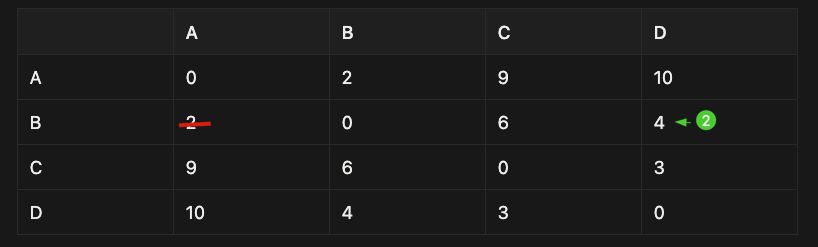

Greedy Example: Nearest Neighbor (for TSP)

Rule:

- Always go to the nearest unvisited city

Start at city A.

Step-by-step:

-

From A, nearest city is B (distance 2)

-

From B, nearest unvisited city is D (distance 4) (note that we can’t return to A now, so we have to move to the next nearest point which is D)

- From D, nearest unvisited city is C (distance 3) (we can’t revisit A and B, so we have to move on to C)

- Return to A (distance 9)

Route: A → B → D → C → A

Total distance = 18

This is easy and fast—but not guaranteed to be the best solution.

4. Dijkstra’s Algorithm (Shortest Path)

What Problem Does It Solve?

Dijkstra’s algorithm finds the shortest path from one starting node to all other nodes.

It answers questions like:

“What is the cheapest way to go from A to D?”

Note that this is different from the previous Traveling salesman problem (in which we need to calculate the best distance combinations to visit all destinations exactly once)

Toy Graph Example

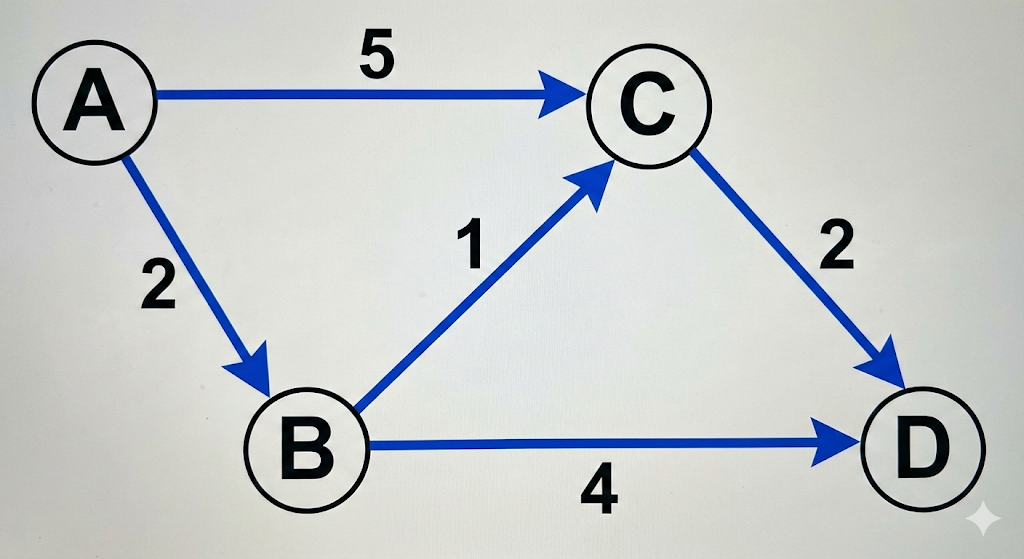

Cities and roads:

- A → B (2)

- A → C (5)

- B → C (1)

- B → D (4)

- C → D (2)

Goal: Find shortest path from A to all others.

Step-by-Step Dijkstra

Step 0: Initialize

A: 0 B: ∞ C: ∞ D: ∞

- Distance to A = 0

- All others = infinity (unknown)

Step 1: Visit A

- A → B = 2

- A → C = 5

Step 2: Visit B (smallest distance so far)

- B → C: 2 + 1 = 3 (update!)

- B → D: 2 + 4 = 6

Step 3: Visit C

- C → D: 3 + 2 = 5 (better than 6, update)

Final shortest distances from A:

A: 0 B: 2 C: 3 D: 5

Key Idea to Remember

Dijkstra’s algorithm:

- Expands outward from the start

- Always picks the closest unvisited node

- Uses greedy thinking, but guarantees correctness (when all edges are non-negative)

5. Minimum Spanning Tree (MST)

What Is a Spanning Tree?

A spanning tree:

- Connects all nodes

- Has no cycles

- Uses the minimum total edge weight

Think of building roads to connect cities as cheaply as possible.

Toy Example

Cities and costs:

- A—B (2)

- A—C (3)

- B—C (1)

- B—D (4)

- C—D (5)

Building an MST (Greedy Idea): Kruskal’s Algorithm

Step 1: Pick the smallest edge → B—C (1)

Step 2: Next smallest → A—B (2)

Step 3: Next smallest that does NOT form a cycle → B—D (4)

- For example, you cannot choose A-C. A–B and B-C already exists, so if you connect A–C it would form a cycle of nodes A, B, C.

Now all cities are connected.

Total cost = 1 + 2 + 4 = 7

6. How These Ideas Connect

| Problem | Algorithm Type |

|---|---|

| TSP | Optimization problem |

| Nearest Neighbor | Greedy heuristic |

| Dijkstra | Shortest path |

| MST | Network optimization |

They all:

- Use graphs

- Use step-by-step decision making

- Balance speed vs optimality

7. Final Takeaways

- Algorithms are recipes for problem-solving

- Graph problems appear everywhere (maps, networks, AI)

- Greedy algorithms are simple and fast

- Dijkstra guarantees shortest paths

- MST minimizes total connection cost

Some advice for Project #2

Dear students,

Project #2 will be on application of Computational Thinking (and most likely recent generative AI tech) in fields outside of computer science. I think this is a good opportunity for you to learn a little something about your own field (and not to mention, to earn good grades if you do well – it’s worth 20% of the grades, equal to the mid-term and the final exams)

My goal here is two-fold. First is to convince you that computer programs and algorithms are absolutely everywhere whether you notice it or not. Second is to guide you on what to and not to do for a good case study.

Let’s talk about music.

As I’m writing this, I’m listening to Hans Zimmer’s F1 Movie Soundtrack, streamed via Spotify on my phone. Not via CD player like in the 90s, not by downloading songs one by one like in the 2000s. Listening to music has dramatically changed since the 2010s, thanks to streaming platforms.

Why has music streaming become so popular? First of all, it’s obviously super convenient to have any song at our fingertips. But I’d argue that there is a more important reason: streaming allows for personalized recommendation.

I like Spotify for the sole reason that it can recommend new songs that I like. If I were to play, say, Ed Sheeran’s Tides, Spotify would recommend Coldplay’s Charlie Brown, which has a similar sound profile and “vibe”. In data science, we call this “content-based filtering”, meaning recommending a new song which is similar to what I have previously liked. The recommendation algorithm is so good that at times it feels like Spotify understands me as if it were my friend. But actually it’s just a very advanced and accurate model: https://youtu.be/pGntmcy_HX8?si=6QfhAlUfk_rmhEl9

I’m not the only users that like Spotify’s music recommendation. Apparently, the recommendation algorithm is one of the key reasons why Spotify has very high user retention rate (https://griffonwebstudios.com/the-secret-sauce-behind-netflix-spotify-and-amazon-hyper-personalization/), that’s a huge advantage for a company that relies on monthly subscriptions to make a profit.

That’s just one example of how computational algorithm changed an industry and benefited a giant company.

If you look for AI+X or computational X where X is marketing, advertising, finance, real estate,… or even chemistry, physics,… or economics, traffic (yes, computer algorithms can be used to solve traffic jams), sports!!, etc. you’re bound to find similar success stories. Or, you might even find failure stories as well, which is also suitable for the project. In fact, it is almost impossible to find any field that hasn’t been impacted by computational thinking or generative AI in some way.

You all did great in the Project #1, but here are some advice from myself to help guide you on Project #2:

- Don’t just list out the “features” or the introduction of a company/ product or go too into too much technical explanation. It’s tempting just to say “Spotify uses both content-based and collaborative filtering. They work using deep learning and stuff…”. This is what infomercials do, and it doesn’t make for an interesting report.

- Find out why a feature or strategy is successful or unsuccessful. For example: users like Spotify’s recommendation because it can find new songs with similar vibes or feelings, not just recommending the same artists or genres again and again.

- Try to specify the impacts of applying computational thinking/AI. For example: users discover new songs more easily thanks to the recommendation, and so they are more likely to keep using Spotify.

- If you find something that is interesting or surprising to you, share it with us. We love to hear what you have learnt. But keep it concise and brief.

Some personal tips on writing a good proposal (Project #2)

This is my personal advice on writing the short proposal for Project #2.

There are many ways to write a proposal, so please note that this is only my way of writing. It’s far from the best writing and you don’t have to follow it if you already know how to write.

That said, if you never had the chance to write a proposal or a plan for an idea (whether it is for class assignment, or research,…), this might be a good place to start.

Why write a proposal at all?

Some ideas sound good in your mind, but you’ll quickly realize that they are bad ideas or are undoable. Writing your idea into a proposal helps to identify these types of ideas, stops you from wasting time on them and lets you focus on the good ones. It will help us to give you timely feedback on your presentation topics too.

Sometimes when you are lucky, your proposal is so good that you only have to follow it to the end, no deviation required. Of course, you may want to change your plan slightly, or even change your entire topic along the way, and that’s okay. Many researchers change their plan like this in the middle of the project (although, it is quite risky and not always recommended). Just make sure to manage your own workload to ensure that you finish the project on time.

Tips on writing a proposal + writing sample

Here’s what I expect to see in a short, 1-2 paragraph proposal (Prof. Cha may want to chime in with his expectations as well):

- The field/industry/area/company/product that your case study is about. For example: Computational Finance, AI + Music recommendation, AI + preventing traffic accidents, AI + cloth try-on in fashion etc.

- What aspect you intend to examine. For example: The technical detail? The macro-effect on the field/industry? The benefit to the company? The impacts on the end users?

- What you expect to learn from the case study. For example: Does AI/ Computational Thinking has a good or bad effect in that case study? What makes it good/bad, or how does AI/CT cause the negative/positive impacts?

Although it is recommended that you include as much details as needed, it is okay if you leave some information vague.

Let’s say I want to report the Spotify case study (AI + music streaming), but I don’t know how Spotify’s recommendation works, or I don’t know exactly how it is beneficial (I just know it’s good for Spotify). Here’s how I would write it:

Our project will study how Spotify uses AI-driven techniques to transform the music streaming industry. We argue that a deeper reason for Spotify’s success is its ability to recommend songs that match each user’s personal taste. ⇒ introduces the field, and the main topic of the case study

First, we will examine how Spotify’s recommendation system works at a high level, and how this technology allows Spotify to create highly personalized playlists. ⇒ one dimension you wish to study, which is the technical detail of Spotify’s algorithm

Second, we will analyze how this recommendation system benefits Spotify’s business model and profitability. ⇒ another dimension to study, which is how the technology helps Spotify business model

Through this case study, we aim to understand how AI technology enables personalized music discovery and why AI-driven personalization has become central to the modern music industry. ⇒ what you expect to learn, which is the impact of AI-driven recommendation on music

However, if I already know a bit about Spotify (that it uses content-based filtering to find similar songs, and its subscription model benefits from a high-retention rate), I can add those details in:

Our project will study how Spotify uses AI-driven techniques to transform the music streaming industry. While streaming became popular for its convenience, we argue that a deeper reason for Spotify’s success is its ability to recommend songs that match each user’s personal taste.

First, we will examine how Spotify’s recommendation system works at a high level, focusing on how the platform analyzes audio features to identify songs that are similar to a user’s listening history. This approach allows Spotify to create highly personalized playlists.

Second, we will analyze how this recommendation capability strengthens Spotify’s subscription-based business model. In particular, we will connect personalized recommendations to Spotify’s high user retention rate, which is crucial for long-term profitability.

Through this case study, we aim to understand how AI technology enables personalized music discovery and why AI-driven personalization has become central to the modern music industry.

Last but not least, be sure to scope your study to fit the 10 minutes and 4 (±1) pages limits. For example, I might be tempted to study and compare the recommendation systems of multiple streaming services (Apple Music, Youtube Music, etc.) but maybe that is too long to fit in, so I’ll just focus on Spotify’s case.

What makes a good startup pitch? (Project #3)

Here’s a sample pitch I’d make if I need to “sell” my current project to investors. Followed by an analysis of what makes it a decent pitch.

The pitch

When I was ten, my father had a serious back injury. He travelled near and far looking for a treatment that would let him sit upright without pain. Eventually, his search took him outside of Vietnam, all the way to Singapore.

Here’s the problem: my father couldn’t speak English. Neither could my mother. And the version of me who could speak confident English, the one who would one day study in Singapore, was still fourteen years in the future.

So he went alone, with a few friends who also couldn’t speak English, and a tour guide who spoke some English but knew almost nothing about healthcare.

I still can’t fully imagine what that must have felt like: being in pain, in a foreign hospital, and almost powerless to explain to your doctor what’s wrong.

And my father’s experience isn’t unique. Every year, thousands of Vietnamese patients travel abroad for treatment, from simple check-ups to complex surgeries. Many Vietnamese patients face the same fear: not being able to communicate clearly with their doctors. And even within Vietnam, many patients need to consult foreign specialists, often through interpreters who lack medical training.

Language barriers make patients anxious. They slow down consultations. They increase the risk of misunderstanding. And they make doctors’ jobs harder.

Fifteen years later, life came full circle. Just days ago, I was put in charge of building a real-time Vietnamese-English medical translation app that helps patients and doctors understand each other instantly – a free, online tool designed to solve the exact problem that haunted my father.

I codenamed it MedComms.

So how does it work?

As I explained in my guest lecture, this is where computational thinking comes in. We break down the translation problem into smaller components, recognizing speech, understanding meaning, and generating clear output, and we train deep neural networks to detect the patterns in each step. These models learn how Vietnamese and English express symptoms, medical terms, and everyday patient language.

With the unique positioning of a Vietnamese- and medical-first research team, we can do what Google Translate can’t: get clinical speech right. Generic translators stumble on medical terminology, misread Vietnamese accents, and produce risky ambiguities. Our system is trained on high-quality speech datasets we collected ourselves at VinUni: real clinical conversations, carefully curated. The result: translations that stay accurate even with overlapping speech, strong accents, or unfamiliar jargon.

And it doesn’t stop there. MedComms improves continuously. As more people use it, we collect crowd-sourced speech contributions from volunteers at the College of Health Sciences — allowing the model to get better, safer, and more reliable over time.

In short, MedComms brings together computational thinking, advanced AI, and trusted in-house medical data to solve one crucial problem: helping Vietnamese patients and foreign doctors understand each other instantly and safely.

Analyzing the pitch

So what makes this a decent start up idea and a good pitch? Well, a startup pitch is simply: here’s a problem, here’s how I’d solve it, and here’s why it would work.

First of all, you may have noticed that I didn’t start with technology, AI or computational techniques – even though we’re in a CT class. I started with a real problem. And all successful startups started the same way: with a real-world problem that demands a solution which hasn’t existed.

The problem can be something that annoys you personally in everyday life. For me, it’s: bad air quality, terrible traffic, time-consuming cooking, etc. For you it might be: how to study with minimal efforts, how to choose your outfit for a given day, etc. Or it can be something larger and more abstract: world peace, sustainable agriculture, international commerce, etc. As long as it is a problem that needs solving, it should be okay for this project.

That said, not all problems are worth solving, because some will have so little impact on so few people that it’s not worth the efforts, and not every problem should be solved with CT, and some problems are impossible to solve. However, if you’re really passionate about a problem and you believe your solution will make a meaningful impact, then go ahead.

Second, I presented a clear, ambitious but achievable solution using computational technology. I envision that inter-lingual communication translation can be achieved via a translation app, so that’s what I’ll be building. I understand that accurate and robust translation can be achieved via neural networks trained on better data, so that’s what I used. Even better, I thought ahead of my competitors and presented a unique competitive advantage compared to existing solutions (being Vietnamese and specialized for medical).

Third, I highlighted how my idea will be used in practice and impact people. I avoided listing out features or focusing on fancy technologies (i.e., becoming an infomercial), because features and technologies themselves can’t solve a problem or improve a situation. For example, “My model can provide two-way English-Vietnamese translation and it’s fine-tuned on medical data.” focuses too much on the features. Instead, my pitch was more about helping patients and doctors to communicate in difficult scenarios.

Fourth, I used a certain structure to lead through my presentation. I usually go with the safe but effective “problem → solution”. But you can go further: “hook → problem → your CT-powered solution → why you → what’s next”.

Real startups also have to explain their finance and how they plan to make money for the long term, but I think it’s outside the scope of this course: we just need to focus on solving problems with CT.

Acknowledgements

The Fall 2025 CECS1031 Computational Thinking course content was created and taught by Professor Sungdeok Cha, who in turn inherited some materials from Assoc. Prof. Kok-Seng Wong. Dr. Nguyen Dang An was my co-TA for the semester.

And of course, appreciation goes to the 24 students who made it through this course. They were fantastic.